British Raj

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Colonial India |

|||||

| Portuguese India | 1510–1961 | ||||

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 | ||||

| Danish India | 1696–1869 | ||||

| French India | 1759–1954 | ||||

| British India 1613–1947 |

|||||

| East India Company | 1612–1757 | ||||

| Company rule in India | 1757–1857 | ||||

| British Raj | 1858–1947 | ||||

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1867 | ||||

| Princely states | 1765–1947 | ||||

| Partition of India | 1947 | ||||

The British Indian Empire or British Raj (rāj in Hindi: राज, Urdu: راج, pronounced: /rɑːdʒ/, lit. "reign"[1]) is the name given to the period of British colonial rule in greater South Asia after the end of the Sepoy Rebellion against the British East India Company when the region including modern India and Pakistan came to be ruled directly by the British Crown; the era is dated to be the era between political epoch events anchored in 1858 and 1947.[2] The term 'British Raj' can also refer to the dominion itself and even the region under the rule.[3] The region, now the nations of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, included areas directly administered by Britain,[4] as well as the princely states ruled by individual rulers under the paramountcy of the British Crown. After 1876, the resulting political union was officially called the Indian Empire and issued passports under that name. As India, it was a founding member of the League of Nations, the United Nations, and a member nation of the Summer Olympics in 1900, 1920, 1928, 1932, and 1936.

The system of governance was instituted in 1858 when the rule of the British East India Company was transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen Victoria (and who in 1876 was proclaimed Empress of India). It lasted until 1947, when the British Indian Empire was partitioned into two sovereign dominion states: the Union of India (later the Republic of India) and the Dominion of Pakistan (later the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the eastern half of which, still later, became the People's Republic of Bangladesh). The province of Burma in the eastern region of the Indian Empire was made a separate colony in 1937 and became independent in 1948.

Contents |

Geographical extent

The British Raj extended over all regions of present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. In addition, at various times, it included Aden Colony (from 1858 to 1937), Lower Burma (from 1858 to 1937), Upper Burma (from 1886 to 1937), British Somaliland (briefly from 1884 to 1898), and Singapore (briefly from 1858 to 1867). Burma was directly administered by the British Crown from 1937 until its independence in 1948. The Trucial States of the Persian Gulf were theoretically princely states of British India until 1946 and used the rupee as their unit of currency.

Among other countries in the region, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) was ceded to Britain in 1802 under the Treaty of Amiens. Ceylon was a British crown colony but not part of British India. The kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan, having fought wars with the British, subsequently signed treaties with them and were recognised by the British as independent states.[5][6] The Kingdom of Sikkim was established as a princely state after the Anglo-Sikkimese Treaty of 1861; however, the issue of sovereignty was left undefined.[7] The Maldive Islands were a British protectorate from 1887 to 1965 but not part of British India.

British India and the Native States

The British Indian Empire (contemporaneously India) consisted of two divisions: British India and the Native States or Princely States. In its Interpretation Act of 1889, the British Parliament adopted the following definitions:

The expression British India shall mean all territories and places within Her Majesty's dominions which are for the time being governed by Her Majesty through the Governor-General of India, or through any Governor or other officer subordinate to the Governor-General of India. The expression India shall mean British India together with any territories of a Native Prince or Chief under the suzerainty of Her Majesty, exercised through the Governor-General of India, or through any Governor or other officer subordinate to the Governor-General of India. (52 & 53 Vict. cap. 63, sec. 18)[8]

In general the term "British India" had been used (and is still used) to also refer to the regions under the rule of the British East India Company in India from 1600 to 1858.[9] The term has also been used to refer to the "British in India".[10]

Suzerainty over 175 princely states, some of the largest and most important, was exercised (in the name of the British Crown) by the central government of British India under the Viceroy; the remaining approximately 500 states were dependents of the provincial governments of British India under a Governor, Lieutenant-Governor, or Chief Commissioner (as the case might have been).[11] A clear distinction between "dominion" and "suzerainty" was supplied by the jurisdiction of the courts of law: the law of British India rested upon the laws passed by the British Parliament and the legislative powers those laws vested in the various governments of British India, both central and local; in contrast, the courts of the Princely States existed under the authority of the respective rulers of those states.[11]

Major provinces

At the turn of the 20th century, British India consisted of eight provinces that were administered either by a Governor or a Lieutenant-Governor. The following table lists their areas and populations (but does not include those of the dependent Native States) circa 1907:[12]

| Province of British India[12] | Area (in thousands of square miles) | Population (in millions of inhabitants) | Chief Administrative Officer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burma | 170 | 9 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Bengal (including present-day Bangladesh, West Bengal, Bihar and Orissa) | 151 | 75 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Madras | 142 | 38 | Governor-in-Council |

| Bombay | 123 | 19 | Governor-in-Council |

| United Provinces (present-day Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand) | 107 | 48 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Central Provinces (including Berar) | 104 | 13 | Chief Commissioner |

| Punjab | 97 | 20 | Lieutenant-Governor |

| Assam | 49 | 6 | Chief Commissioner |

During the partition of Bengal (1905–1911), a new province, Assam and East Bengal was created as a Lieutenant-Governorship. In 1911, East Bengal was reunited with Bengal, and the new provinces in the east became: Assam, Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.[12]

Minor provinces

In addition, there were a few minor provinces that were administered by a Chief Commissioner:[13]

| Minor Province | Area (in thousands of square miles) | Population (in thousands of inhabitants) | Chief Administrative Officer |

|---|---|---|---|

| North West Frontier Province | 16 | 2,125 | Chief Commissioner |

| British Baluchistan (British and Administered territory) | 46 | 308 | British Political Agent in Baluchistan served as ex-officio Chief Commissioner |

| Coorg | 1.6 | 181 | British Resident in Mysore served as ex-officio Chief Commissioner |

| Ajmer-Merwara | 2.7 | 477 | British Political Agent in Rajputana served as ex-officio Chief Commissioner |

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | 3 | 25 | Chief Commissioner |

Princely states

A Princely State, also called Native State or Indian State, was a nominally sovereign entity of British rule in India that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule such as suzerainty or paramountcy. Military, foreign affairs, and communications power were under British control. There were 565 princely states when the Indian subcontinent became independent from Britain in August 1947.[14]

Organization

Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Act for the Better Government of India (1858) made changes in the governance of India at three levels: in the imperial government in London, in the central government in Calcutta, and in the provincial governments in the presidencies (and later in the provinces).[15]

In London, it provided for a cabinet-level Secretary of State for India and a fifteen-member Council of India, whose members were required, as one prerequisite of membership, to have spent at least ten years in India and to have done so no more than ten years before.[16] Although the Secretary of State formulated the policy instructions to be communicated to India, he was required in most instances to consult the Council, but especially so in matters relating to spending of Indian revenues.[15] The Act envisaged a system of "double government" in which the Council ideally served both as a check on excesses in imperial policy-making and as a body of up-to-date expertise on India.[15] However, the Secretary of State also had special emergency powers that allowed him to make unilateral decisions, and, in reality, the Council's expertise was sometimes outdated.[17] From 1858 until 1947, twenty seven individuals served as Secretary of State for India and directed the India Office; these included: Sir Charles Wood (1859–1866), Marquess of Salisbury (1874–1878) (later Prime Minister of Britain), John Morley (1905–1910) (initiator of the Minto-Morley Reforms), E. S. Montagu (1917–1922) (an architect of the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms), and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence (1945–1947) (head of the 1946 Cabinet Mission to India). The size of the advisory Council was reduced over the next half-century, but its powers remained unchanged. In 1907, for the first time, two Indians were appointed to the Council.[18]

In Calcutta, the Governor-General remained head of the Government of India and now was more commonly called the Viceroy on account of his secondary role as the Crown's representative to the nominally sovereign princely states; he was, however, now responsible to the Secretary of State in London and through him to Parliament. A system of "double government" had already been in place during the Company's rule in India from the time of Pitt's India Act of 1784.[18] The Governor-General in the capital, Calcutta, and the Governor in a subordinate presidency (Madras or Bombay) was each required to consult his advisory council; executive orders in Calcutta, for example, were issued in the name of "Governor-General-in-Council" (i.e. the Governor-General with the advice of the Council).[18] The Company's system of "double government" had its critics, since, from the time of the system's inception, there had been intermittent feuding between the Governor-General and his Council; still, the Act of 1858 made no major changes in governance.[18] However, in the years immediately thereafter, which were also the years of post-rebellion reconstruction, the Viceroy Lord Canning found the collective decision-making of the Council to be too time-consuming for the pressing tasks ahead.[18] He therefore requested the "portfolio system" of an Executive Council in which the business of each government department (the "portfolio") was assigned to and became the responsibility of a single Council member.[18] Routine departmental decisions were made exclusively by the member; however, important decisions required the consent of the Governor-General and, in the absence of such consent, required discussion by the entire Executive Council. This innovation in Indian governance was promulgated in the Indian Councils Act of 1861.

If the Government of India needed to enact new laws, the Councils Act allowed for a Legislative Council—an expansion of the Executive Council by up to twelve additional members, each appointed to a two-year term—with half the members consisting of British officials of the government (termed official) and allowed to vote, and the other half, comprising Indians and domiciled Britons in India (termed non-official) and serving only in an advisory capacity.[19] All laws enacted by Legislative Councils in India, whether by the Imperial Legislative Council in Calcutta or by the provincial ones in Madras and Bombay, required the final assent of the Secretary of State in London; this prompted Sir Charles Wood, the second Secretary of State, to describe the Government of India as "a despotism controlled from home".[20] Moreover, although the appointment of Indians to the Legislative Council was a response to calls after the 1857 rebellion, most notably by Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan, for more consultation with Indians, the Indians so appointed were from the landed aristocracy, often chosen for their loyalty, and far from representative.[21] Even so, the ..."...tiny advances in the practise of representative government were intended to provide safety valves for the expression of public opinion which had been so badly misjudged before the rebellion".[22] Indian affairs now also came to be more closely examined in the British Parliament and more widely discussed in the British press.[23]

Although the Great Uprising of 1857 had shaken the British enterprise in India, it had not derailed it. After the rebellion, the British became more circumspect. Much thought was devoted to the causes of the rebellion, and from it three main lessons were drawn. At a more practical level, it was felt that there needed to be more communication and camaraderie between the British and Indians—not just between British army officers and their Indian staff but in civilian life as well. The Indian army was completely reorganised: units composed of the Muslims and Brahmins of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, who had formed the core of the rebellion, were disbanded.[24] New regiments, like the Sikhs and Baluchis, composed of Indians who, in British estimation, had demonstrated steadfastness, were formed. From then on, the Indian army was to remain unchanged in its organisation until 1947.[25] The 1861 Census had revealed that the English population in India was 125,945. Of these only about 41,862 were civilians as compared with about 84,083 European officers and men of the Army.[26] In 1880, the standing Indian Army consisted of 66,000 British soldiers, 130,000 Natives, and 350,000 soldiers in the princely armies.[27]

It was also felt that both the princes and the large land-holders, by not joining the rebellion, had proved to be, in Lord Canning's words, "breakwaters in a storm".[24] They too were rewarded in the new British Raj by being officially recognised in the treaties each state now signed with the Crown.[25] At the same time, it was felt that the peasants, for whose benefit the large land-reforms of the United Provinces had been undertaken, had shown disloyalty, by, in many cases, fighting for their former landlords against the British. Consequently, no more land reforms were implemented for the next 90 years: Bengal and Bihar were to remain the realms of large land holdings (unlike the Punjab and Uttar Pradesh).[25]

Lastly, the British felt disenchanted with Indian reaction to social change. Until the rebellion, they had enthusiastically pushed through social reform, like the ban on suttee by Lord William Bentinck.[24] It was now felt that traditions and customs in India were too strong and too rigid to be changed easily; consequently, no more British social interventions were made, especially in matters dealing with religion, even when the British felt very strongly about the issue (as in the instance of the remarriage of Hindu child widows).[25]

Famines, epidemics, and public health

During the British Raj, India experienced some of the worst famines ever recorded, including the Great Famine of 1876–78, in which 6.1 million to 10.3 million people died[28] and the Indian famine of 1899–1900, in which 1.25 to 10 million people died.[28] Recent research, including work by Mike Davis and Amartya Sen,[29] attribute most of the effects of these famines to British policy in India.

Having been criticised for the badly bungled relief effort during the Orissa famine of 1866,[30] British authorities began to discuss famine policy soon afterwards, and, in early 1868, Sir William Muir, Lieutenant-Governor of Agra Province, issued a famous order stating that:[31]

"...every District officer would be held personally responsible that no deaths occurred from starvation which could have been avoided by any exertion or arrangement on his part or that of his subordinates."

The first cholera pandemic began in Bengal, then spread across India by 1820. 10,000 British troops and countless Indians died during this pandemic.[32] Deaths in India between 1817 and 1860 are estimated to have exceeded 15 million persons. Another 23 million died between 1865 and 1917.[33] The Third Pandemic of plague started in China in the middle of the 19th century, spreading disease to all inhabited continents and killing 10 million people in India alone.[34] Waldemar Haffkine, who mainly worked in India, was the first microbiologist who developed and used vaccines against cholera and bubonic plague. In 1925, the Plague Laboratory in Bombay was renamed the Haffkine Institute.

Fevers had been considered one of the leading causes of death in India in the 19th century.[35] It was Britain's Sir Ronald Ross working in the Presidency General Hospital in Calcutta who finally proved in 1898 that malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes.[36] In 1881, around 120,000 leprosy patients existed in India. The central government passed the Lepers Act of 1898, which provided legal provision for forcible confinement of leprosy sufferers in India.[37] Under the direction of Mountstuart Elphinstone a program was launched to propagate smallpox vaccination.[38] Mass vaccination in India resulted in a major decline in smallpox mortality by the end of the 19th century.[39] In 1849 nearly 13% of all Calcutta deaths were due to smallpox.[40] Between 1868 and 1907, there were approximately 4.7 million deaths from smallpox.[41]

Sir Robert Grant directed his attention to the expediency of establishing a systematic institution in the Bombay for imparting medical knowledge to the natives.[42] In 1860, Grant Medical College became one of the four recognised colleges for teaching courses leading to degrees (others being Elphinstone College, Deccan College and Government Law College, Mumbai).

Economic impact

Debate continues about the economic impact of British imperialism on India. The issue was actually raised by conservative British politician Edmund Burke who in the 1780s vehemently attacked the East India Company, claiming that Warren Hastings and other top officials had ruined the Indian economy and society. Indian historian Rajat Kanta Ray (1998) continues this line of attack, saying the new economy brought by the British in the 18th century was a form of "plunder" and a catastrophe for the traditional economy of Mughal India. Ray accuses the British of depleting the food and money stocks and imposing high taxes that helped cause the terrible famine of 1770, which killed a third of the people of Bengal.[43]

P. J. Marshall shows that recent scholarship has reinterpreted the view that the prosperity of the formerly benign Mughal rule gave way to poverty and anarchy. Marshall argues the British takeover did not make any sharp break with the past. British control was delegated largely through regional Mughal rulers and was sustained by a generally prosperous economy for the rest of the 18th century. Marshall notes the British went into partnership with Indian bankers and raised revenue through local tax administrators and kept the old Mughal rates of taxation.[44] Instead of the Indian nationalist account of the British as alien aggressors, seizing power by brute force and impoverishing all of India, Marshall presents the interpretation, supported by many scholars in India and the West, in which the British were not in full control but instead were players in what was primarily an Indian play and in which their rise to power depended upon excellent cooperation with Indian elites. Marshall admits that much of his interpretation is still rejected by many historians working in India, who prefer to 'bash the British'.[45]

Timeline

| Viceroy | Period of Tenure | Events/Accomplishments |

|---|---|---|

| Charles Canning | 1 Nov 1858 21 Mar 1862 |

1858 reorganisation of British Indian Army (contemporaneously and hereafter Indian Army) Construction begins (1860): University of Bombay, University of Madras, and University of Calcutta Indian Penal Code passed into law in 1860. Upper Doab famine of 1860–61 Indian Councils Act 1861 Establishment of Archaeological Survey of India in 1861 James Wilson, financial member of Council of India reorganises customs, imposes income tax, creates paper currency. Indian Police Act of 1861, creation of Imperial Police later known as Indian Police Service. |

| Lord Elgin | 21 Mar 1862 20 Nov 1863 |

Dies prematurely in Dharamsala |

| Sir John Lawrence | 12 Jan 1864 12 Jan 1869 |

Anglo-Bhutan Duar War (1864–1865) Orissa famine of 1866 Rajputana famine of 1869 Creation of Department of Irrigation. Creation of Imperial Forestry Service in 1867 (now Indian Forest Service). |

| Lord Mayo | 12 Jan 1869 8 Feb 1872 |

Creation of Department of Agriculture (now Ministry of Agriculture) Major extension of railways, roads, and canals Indian Councils Act of 1870 Creation of Andaman and Nicobar Islands as a Chief Commissionership (1872). Assassination of Lord Mayo in the Andamans. |

| Lord Northbrook | 3 May 1872 12 Apr 1876 |

Mortalities in Bihar famine of 1873–74 prevented by importation of rice from Burma. Gaikwad of Baroda dethroned for misgovernment; dominions continued to a child ruler. Indian Councils Act of 1874 Visit of the Prince of Wales, future Edward VII in 1875–76. |

| Lord Lytton | 12 Apr 1876 8 Jun 1880 |

Baluchistan established as a Chief Commissionership Queen Victoria (in absentia) proclaimed Empress of India at Delhi Durbar of 1877. Great Famine of 1876–78: 5.25 million dead; reduced relief offered at expense of Rs. 8 crore. Creation of Famine Commission of 1878–80 under Sir Richard Strachey. Indian Forest Act of 1878 Second Anglo-Afghan War. |

| Lord Ripon | 8 Jun 1880 13 Dec 1884 |

End of Second Anglo-Afghan War. Repeal of Vernacular Press Act of 1878. Compromise on the Ilbert Bill. Local Government Acts extend self-government from towns to country. University of Punjab established in Lahore in 1882 Famine Code promulgated in 1883 by the Government of India. Creation of the Education Commission. Creation of indigenous schools, especially for Muslims. Repeal of import duties on cotton and of most tariffs. Railway extension. |

| Lord Dufferin | 13 Dec 1884 10 Dec 1888 |

Passage of Bengal Tenancy Bill Third Anglo-Burmese War. Joint Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission appointed for the Afghan frontier. Russian attack on Afghans at Panjdeh (1885). The Great Game in full play. Report of Public Services Commission of 1886-87, creation of Imperial Civil Service (later Indian Civil Service, and today Indian Administrative Service) University of Allahabad established in 1887 Queen Victoria's Jubilee, 1887. |

| Lord Lansdowne | 10 Dec 1888 11 Oct 1894 |

Strengthening of NW Frontier defence. Creation of Imperial Service Troops consisting of regiments contributed by the princely states. Gilgit Agency leased in 1899 British Parliament passes Indian Councils Act of 1892 opening the Imperial Legislative Council to Indians. Revolution in princely state of Manipur and subsequent reinstatement of ruler. High point of The Great Game. Establishment of the Durand Line between British India and Afghanistan, Railways, roads, and irrigation works begun in Burma. Border between Burma and Siam finalised in 1893. Fall of the Rupee, resulting from the steady depreciation of silver currency worldwide (1873–93). Indian Prisons Act of 1894 |

| Lord Elgin | 11 Oct 1894 6 Jan 1899 |

Reorganization of Indian Army (from Presidency System to the four Commands). Pamir agreement Russia, 1895 The Chitral Campaign (1895), the Tirah Campaign (1896–97) Indian famine of 1896–97 beginning in Bundelkhand. Bubonic plague in Bombay (1896), Bubonic plague in Calcutta (1898); riots in wake of plague prevention measures. Establishment of Provincial Legislative Councils in Burma and Punjab; the former a new Lieutenant Governorship. |

| Lord Curzon | 6 Jan 1899 18 Nov 1905 |

Creation of the North West Frontier Province (now Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa) under a Chief Commissioner (1901). Indian famine of 1899–1900. Return of the bubonic plague, 1 million deaths Financial Reform Act of 1899; Gold Reserve Fund created for India. Punjab Land Alienation Act Inauguration of Department (now Ministry) of Commerce and Industry. Death of Queen Victoria (1901); dedication of the Victoria Memorial Hall, Calcutta as a national gallery of Indian antiquities, art, and history. Coronation Durbar in Delhi (1903); Edward VII (in absentia) proclaimed Emperor of India. Francis Younghusband's British expedition to Tibet (1903–04) North-Western Provinces (previously Ceded and Conquered Provinces) and Oudh renamed United Provinces in 1904 Reorganization of Indian Universities Act (1904). Systemization of preservation and restoration of ancient monuments by Archaeological Survey of India with Indian Ancient Monument Preservation Act. Inauguration of agricultural banking with Cooperative Credit Societies Act of 1904 Partition of Bengal (1905); new province of East Bengal and Assam under a Lieutenant-Governor. |

| Lord Minto | 18 Nov 1905 23 Nov 1910 |

Creation of the Railway Board Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 Government of India Act of 1909 (also Minto-Morley Reforms) Appointment of Indian Factories Commission in 1909. Establishment of Department of Education in 1910 (now Ministry of Education) |

| Lord Hardinge | 23 Nov 1910 4 Apr 1916 |

Visit of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911: commemoration as Emperor and Empress of India at last Delhi Durbar King George V announces creation of new city of New Delhi to replace Calcutta as capital of India. Indian High Courts Act of 1911 Indian Factories Act of 1911 Construction of New Delhi, 1912-1929 World War I, Indian Army in: Western Front, Belgium, 1914; German East Africa (Battle of Tanga, 1914); Mesopotamian Campaign (Battle of Ctesiphon, 1915; Siege of Kut, 1915-16); Battle of Galliopoli, 1915-16 Passage of Defence of India Act 1915 |

| Lord Chelmsford | 4 Apr 1916 2 Apr 1921 |

Indian Army in: Mesopotamian Campaign (Fall of Baghdad, 1917); Sinai and Palestine Campaign (Battle of Megiddo, 1918) Passage of Rowlatt Act, 1919 Government of India Act of 1919 (also Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms) Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, 1919 Third Anglo-Afghan War, 1919 University of Rangoon established in 1920. |

| Lord Reading | 2 Apr 1921 3 Apr 1926 |

University of Delhi established in 1922. Indian Workers Compensation Act of 1923 |

| Lord Irwin | 3 Apr 1926 18 Apr 1931 |

Indian Trade Unions Act of 1926, Indian Forest Act, 1927 Appointment of Royal Commission of Indian Labour, 1929 Indian Constitutional Round Table Conferences, London, 1930-32, Gandhi-Irwin Pact, 1931. |

| Lord Willingdon | 18 Apr 1931 18 Apr 1936 |

New Delhi inaugurated as capital of India, 1931. Indian Workmen's Compensation Act of 1933 Indian Factories Act of 1934 Royal Indian Air Force created in 1932. Indian Military Academy established in 1932. Government of India Act of 1935 Creation of Reserve Bank of India |

| Lord Linlithgow | 18 Apr 1936 1 Oct 1943 |

Indian Payment of Wages Act of 1936 Burma administered independently after 1937 with creation of new cabinet position Secretary of State for India and Burma Indian Provincial Elections of 1937 Cripps' mission to India, 1942. Indian Army in Middle East Theatre of World War II (East African campaign, 1940, Anglo-Iraqi War, 1941, Syria-Lebanon campaign, 1941, Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran, 1941 Indian Army in North African campaign (Operation Compass, Operation Crusader, First Battle of El Alamein, Second Battle of El Alamein) |

| Lord Wavell | 1 Oct 1943 21 Feb 1947 |

Indian Army becomes, at 2.5 million men, the largest all-volunteer force in history. World War II: Burma Campaign, 1943-45 (Battle of Kohima, Battle of Imphal) Bengal famine of 1943 Indian Army in Italian campaign (Battle of Monte Cassino) British Labour Party wins UK General Election of 1945 with Clement Attlee as prime minister. 1946 Cabinet Mission to India Indian Elections of 1946. |

| Lord Mountbatten | 21 Feb 1947 15 Aug 1947 |

Indian Independence Act 1947 (10 and 11 Geo VI, c. 30) of the British Parliament enacted on 18 July 1947. Radcliffe Award, August 1947 Partition of India India Office changed to Burma Office, and Secretary of State for India and Burma to Secretary of State for Burma. |

History

Company rule in India

Although the British East India Company had administered its factory areas in India—beginning with Surat early in the 17th century, and including by the century's end, Fort William near Calcutta, Fort St George in Madras and the Bombay Castle—its victory in the Battle of Plassey in 1757 marked the real beginning of the Company rule in India. The victory was consolidated in 1764 at the Battle of Buxar (in Bihar), when the defeated Mughal emperor, Shah Alam II, granted the Company the Diwani ("right to collect land-revenue") in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. The Company soon expanded its territories around its bases in Bombay and Madras: the Anglo-Mysore Wars (1766–1799) and the Anglo-Maratha Wars (1772–1818) gave it control over most of India south of the Narmada River.

Earlier, in 1773, the British Parliament granted regulatory control over East India Company to the British government and established the post of Governor-General of India, with Warren Hastings as the first incumbent.[46] In 1784, the British Parliament passed Pitt's India Act, which created a Board of Control for overseeing the administration of East India Company. Hastings was succeeded in 1784 by Lord Cornwallis, who promulgated the 'Permanent Settlement of Bengal' with the zamindars.

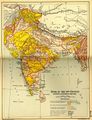

Map of India showing British Expansion between 1805 and 1910 |

Lord Cornwallis, the Governor-General who established the Permanent Settlement in Bengal |

Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, who rapidly expanded the Company's territories with victories in the Anglo-Maratha Wars and Anglo-Mysore Wars |

At the turn of the 19th century, Governor-General Wellesley began what became two decades of accelerated expansion of Company territories.[47] This was achieved either by subsidiary alliances between the Company and local rulers or by direct military annexation. The subsidiary alliances created the Princely States (or Native States) of the Hindu Maharajas and the Muslim Nawabs, prominent among which were: Cochin (1791), Jaipur (1794), Travancore (1795), Hyderabad (1798), Mysore (1799), Cis-Sutlej Hill States (1815), Central India Agency (1819), Kutch and Gujarat Gaikwad territories (1819), Rajputana (1818), and Bahawalpur (1833).[47] The annexed regions included the North Western Provinces (comprising Rohilkhand, Gorakhpur, and the Doab) (1801), Delhi (1803), and Sindh (1843). Punjab, Northwest Frontier Province, and Kashmir, were annexed after the Anglo-Sikh Wars in 1849; however, Kashmir was immediately sold under the Treaty of Amritsar (1850) to the Dogra Dynasty of Jammu, and thereby became a princely state. In 1854 Berar was annexed, and the state of Oudh two years later.[47]

The East India Company also signed treaties with various Afghan rulers and with Ranjit Singh of Lahore to counterbalance the Russian support of Persia's plans in western Afghanistan. In 1839, the Company's effort to more actively support Shah Shuja as Amir in Afghanistan, led to the First Afghan War (1839–42) and resulted in a military disaster for it. As the British expanded their territory in India, so did Russia in Central Asia with the taking of Bukhara and Samarkand in 1863 and 1868 respectively, and thereby setting the stage for The Great Game of Central Asia.[48]

In the Charter Act of 1813, the British parliament renewed the Company's charter but terminated its monopoly, opening India to both private investment and missionary work.[47] With increased British power in India, supervision of Indian affairs by the British Crown and Parliament increased as well; by the 1820s, British nationals could transact business under the protection of the Crown in the three Company presidencies.[47] In the Charter Act of 1833, the British parliament revoked the Company's trade license altogether, making the Company a part of British governance, although the administration of British India remained the province of Company officers.[49]

Starting in 1772, the Company began a series of land revenue "settlements," which made major changes in landed rights and rural economy in India. In 1793, the Governor-General Lord Cornwallis promulgated the permanent settlement in the Bengal Presidency, the first socio-economic regulation in colonial India.[50] It was named permanent because it fixed the land tax in perpetuity in return for landed property rights for a class of intermediaries called zamindars, who thereafter became owners of the land.[50] It was hoped that knowledge of a fixed government demand would encourage the zamindars to increase both their average outcrop and the land under cultivation, since they would be able to retain the profits from the increased output; in addition, the land itself would become a marketable form of property that could be purchased, sold, or mortgaged.[51] However, the zamindars themselves were often unable to meet the increased demands that the Company had placed on them; consequently, many defaulted, and by one estimate, up to one-third of their lands were auctioned during the first three decades following the permanent settlement.[52] In southern India, Thomas Munro, who would later become Governor of Madras, promoted the ryotwari system, in which the government settled land-revenue directly with the peasant farmers, or ryots.[51] Based on the utilitarian ideas of James Mill, who supervised the Company's land revenue policy during 1819-1830, and David Ricardo's Law of Rent, it was considered by its supporters to be both closer to traditional practice and more progressive, allowing the benefits of Company rule to reach the lowest levels of rural society.[51] However, in spite of the appeal of the ryotwari system's abstract principles, class hierarchies in southern Indian villages had not entirely disappeared—for example village headmen continued to hold sway—and peasant cultivators came to experience revenue demands they could not meet.[53]

Land revenue settlements constituted a major administrative activity of the various governments in India under Company rule.[54] In all areas other than the Bengal Presidency, land settlement work involved a continually repetitive process of surveying and measuring plots, assessing their quality, and recording landed rights, and constituted a large proportion of the work of Indian Civil Service officers working for the government.[54] After the Company lost its trading rights, it became the single most important source of government revenue, roughly half of overall revenue in the middle of the 19th century.[54] Since, in many regions, the land tax assessment could be revised, and since it was generally computed at a high level, it created lasting resentment that later came to a head in the rebellion that rocked much of North India in 1857.[55]

Indian rebellion of 1857

The rebellion (also known as the Indian Mutiny) began with mutinies by sepoys of the Bengal Presidency army; in 1857 the presidency consisted of present-day Bangladesh, and the Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (UP). However, most rebel soldiers were from the UP region, and, in particular, from Northwest Provinces (especially, Ganga-Jumna Doab) and Oudh, and many came from landowning families.[56] Within weeks of the initial mutinies—as the rebel soldiers wrested control of many urban garrisons from the British—the rebellion was joined by various discontented groups in the hinterlands, in both farmed areas and the backwoods. The latter group, forming the civilian rebellion, consisted of feudal nobility, landlords, peasants, rural merchants, and some tribal groups.[57]

Lord Dalhousie, the Governor-General of India from 1848 to 1856, who devised the Doctrine of Lapse |

Lakshmibai, The Rani of Jhansi, one of the principal leaders of the rebellion who earlier had lost her kingdom as a result of the Doctrine of Lapse |

"Interior of the Secundra Bagh after the Slaughter of 2,000 Rebels by the 93rd Highlanders and 4th Punjab Regiment." - Felice Beato in 1858. |

After the annexation of Oudh by the East India Company in 1856, many sepoys were disquieted both from losing their perquisites as landed gentry in the Oudh courts and from the anticipation of any increased land-revenue payments that the annexation might augur.[58] Some Indian soldiers, misreading the presence of missionaries as a sign of official intent, were persuaded that the East India Company was masterminding mass conversions of Hindus and Muslims to Christianity.[59] Changes in the terms of their professional service may also have created resentment. As the extent of British jurisdiction expanded with British victories in wars and with annexation of territory, the soldiers were now not only expected to serve in less familiar regions (such as Lower Burma after the Second Burmese War in 1852-53), but also make do without the "foreign service" remuneration that had previously been their due.[60]

The civilian rebellion was more multifarious in origin. The rebels consisted of three groups: feudal nobility, rural landlords called taluqdars, and the peasants. The nobility, many of whom had lost titles and domains under the Doctrine of Lapse, which derecognised adopted children of princes as legal heirs, felt that the British had interfered with a traditional system of inheritance. Rebel leaders such as Nana Sahib and the Rani of Jhansi belonged to this group; the latter, for example, was prepared to accept British paramountcy if her adopted son was recognised as the heir.[61] The second group, the taluqdars had lost half their landed estates to peasant farmers as a result of the land reforms that came in the wake of annexation of Oudh. As the rebellion gained ground, the taluqdars quickly reoccupied the lands they had lost, and paradoxically, in part due to ties of kinship and feudal loyalty, did not experience significant opposition from the peasant farmers, many of whom too now joined the rebellion to the great dismay of the British.[62] Heavy land-revenue assessment in some areas by the British may have resulted in many landowning families either losing their land or going into great debt with money lenders, and providing ultimately a reason to rebel; money lenders, in addition to the British, were particular objects of the rebels' animosity.[63] The civilian rebellion was also highly uneven in its geographic distribution, even in areas of north-central India that were no longer under British control. For example, the relatively prosperous Muzaffarnagar district, a beneficiary of a British irrigation scheme, and next door to Meerut where the upheaval began, stayed mostly calm throughout.[64]

Economic and political changes

In the second half of the 19th century, both the direct administration of India by the British crown and the technological change ushered in by the industrial revolution, had the effect of closely intertwining the economies of India and Britain.[65] In fact many of the major changes in transport and communications (that are typically associated with Crown Rule of India) had already begun before the Mutiny. Since Dalhousie had embraced the technological change then rampant in Britain, India too saw rapid development of all those technologies. Railways, roads, canals, and bridges were rapidly built in India and telegraph links equally rapidly established in order that raw materials, such as cotton, from India's hinterland could be transported more efficiently to ports, such as Bombay, for subsequent export to England.[66] Likewise, finished goods from England were transported back just as efficiently, for sale in the burgeoning Indian markets.[67] However, unlike Britain itself, where the market risks for the infrastructure development were borne by private investors, in India, it was the taxpayers—primarily farmers and farm-labourers—who endured the risks, which, in the end, amounted to £50 million.[68] In spite of these costs, very little skilled employment was created for Indians.

The rush of technology was also changing the agricultural economy in India: by the last decade of the 19th century, a large fraction of some raw materials—not only cotton, but also some food-grains—were being exported to faraway markets.[69] Consequently, many small farmers, dependent on the whims of those markets, lost land, animals, and equipment to money-lenders.[69] More tellingly, the latter half of the 19th century also saw an increase in the number of large-scale famines in India. Although famines were not new to the subcontinent, these were particularly severe, with tens of millions dying, and with many critics, both British and Indian, laying the blame at the doorsteps of the lumbering colonial administrations.[70]

Taxes in India decreased during the colonial period for most of India's population; with the land tax revenue claiming 15% of India's national income during Mogul times compared with 1% at the end of the colonial period. The percentage of national income for the village economy increased from 44% during Mogul times to 54% by the end of colonial period. India's per capita GDP decreased from $550 in 1700 to $520 by 1857, although it had increased to $618 by 1947[71]

Railways

In 1844, the Governor-General of India Lord Hardinge allowed private entrepreneurs to set up a rail system in India. The East India Company (and later the British Government) encouraged new railway companies backed by private investors under a scheme that would provide land and guarantee an annual return of up to five percent during the initial years of operation. The companies were to build and operate the lines under a 99 year lease, with the government having the option to buy them earlier.[72]

Two new railway companies, Great Indian Peninsular Railway (GIPR) and East Indian Railway (EIR), were created in 1853-54 to construct and operate two 'experimental' lines near Bombay and Calcutta respectively.[72] The first train in India had become operational on 22 December 1851 for localised hauling of canal construction material in Roorkee.[73] A year and a half later, on 16 April 1853, the first passenger train service was inaugurated between Bori Bunder in Bombay and Thane covering a distance of 34 kilometres (21 mi).[74]

In 1854 Lord Dalhousie, the then Governor-General of India, formulated a plan to construct a network of trunk lines connecting the principal regions of India. Encouraged by the government guarantees, investment flowed in and a series of new rail companies were established, leading to rapid expansion of the rail system in India.[75] Soon various native states built their own rail systems and the network spread to the regions that became the modern-day states of Assam, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh. The route mileage of this network increased from 1,349 kilometres (838 mi) in 1860 to 25,495 kilometres (15,842 mi) in 1880 - mostly radiating inland from the three major port cities of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta.[76] Most of the railway construction was done by Indian companies. The railway line from Lahore to Delhi was done B.S.D. Bedi and Sons (Baba Shib Dayal Bedi), this included the building of the Jamuna Bridge. By 1895, India had started building its own locomotives, and in 1896 sent engineers and locomotives to help build the Uganda Railway.

At the beginning of the 20th century India had a multitude of rail services with diverse ownership and management, operating on broad, metre and narrow gauge networks.[77] In 1900 the government took over the GIPR network, while the company continued to manage it. With the arrival of the First World War, the railways were used to transport troops and foodgrains to the port city of Bombay and Karachi en route to UK, Mesopotamia and East Africa. By the end of the First World War, the railways had suffered immensely and were in a poor state.[78] In 1923, both GIPR and EIR were nationalised with the state assuming both ownership and management control.[77] The Second World War severely crippled the railways as rolling stock was diverted to the Middle East, and the railway workshops were converted into munitions workshops.[79] After independence in 1947, forty-two separate railway systems, including thirty-two lines owned by the former Indian princely states, were amalgamated as a single unit, which was christened as the Indian Railways - by now it had become the fourth longest railway network in the world.

The 1909 Map of Indian Railways, when India had the fourth largest railway network in the world. Railway construction in India began in 1853. |

"The most magnificent railway station in the world." Stereographic image of Victoria Terminus, Bombay, which was completed in 1888 |

The Agra canal (c. 1873), a year away from completion. The canal was closed to navigation in 1904 in order to increase irrigation and aid in famine-prevention. |

Beginnings of self-government

The first steps were taken toward self-government in British India in the late 19th century with the appointment of Indian counsellors to advise the British viceroy and the establishment of provincial councils with Indian members; the British subsequently widened participation in legislative councils with the Indian Councils Act of 1892. Municipal Corporations and District Boards were created for local administration; they included elected Indian members.

The Government of India Act of 1909 — also known as the Morley-Minto Reforms (John Morley was the secretary of state for India, and Gilbert Elliot, fourth earl of Minto, was viceroy) — gave Indians limited roles in the central and provincial legislatures, known as legislative councils. Indians had previously been appointed to legislative councils, but after the reforms some were elected to them. At the centre, the majority of council members continued to be government-appointed officials, and the viceroy was in no way responsible to the legislature. At the provincial level, the elected members, together with unofficial appointees, outnumbered the appointed officials, but responsibility of the governor to the legislature was not contemplated. Morley made it clear in introducing the legislation to the British Parliament that parliamentary self-government was not the goal of the British government.

The Morley-Minto Reforms were a milestone. Step by step, the elective principle was introduced for membership in Indian legislative councils. The "electorate" was limited, however, to a small group of upper-class Indians. These elected members increasingly became an "opposition" to the "official government". The Communal electorates were later extended to other communities and made a political factor of the Indian tendency toward group identification through religion.

John Morley, the Secretary of State for India from 1905 to 1910, and Gladstonian Liberal. The Government of India Act of 1909, also known as the Minto-Morley Reforms allowed Indians to be elected to the Legislative Council. |

Picture post card of the Gordon Highlanders marching past King George V and Queen Mary at the Delhi Durbar on 12 December 1911, when the King was crowned Emperor of India |

Indian medical orderlies attending to wounded soldiers with the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force in Mesopotamia during World War I |

World War I and its aftermath

World War I proved to be a watershed in the imperial relationship between Britain and India. 1.4 million Indian and British soldiers of the British Indian Army took part in the war and their participation had a wider cultural fallout: news of Indian soldiers fighting and dying with British soldiers, and soldiers from dominions like Canada and Australia, travelled to distant corners of the world both in newsprint and by the new medium of the radio.[80] India’s international profile thereby rose and continued to rise during the 1920s.[80] It was to lead, among other things, to India, under its own name, becoming a founding member of the League of Nations in 1920 and participating, under the name, "Les Indes Anglaises" (the British Indies), in the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp.[81] Back in India, especially among the leaders of the Indian National Congress, it led to calls for greater self-government for Indians.[80]

In 1916, the moderate nationalists demonstrated new strength with the signing of the Lucknow Pact and the founding of the Home Rule leagues. With the realisation, after the disaster in the Mesopotamian campaign, that the war would likely last longer, the new Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, cautioned that the Government of India needed to be more responsive to Indian opinion.[82] Towards the end of the year, after discussions with the government in London, he suggested that the British demonstrate their good faith in light of the Indian war role through a number of public actions. The actions he suggested included awards of titles and honours to princes, granting of commissions in the army to Indians, and removal of the much-reviled cotton excise duty. Most importantly, he suggested an announcement of Britain's future plans for India and an indication of some concrete steps.[82] After more discussion, in August 1917, the new Liberal Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, announced the British aim of “increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration, and the gradual development of self-governing institutions, with a view to the progressive realisation of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire.”[82] Although the plan envisioned limited self-government at first only in the provinces – with India emphatically within the British Empire – it represented the first British proposal for any form of representative government in a non-white colony.[82]

Earlier, at the onset of World War I, the reassignment of most of the British army in India to Europe and Mesopotamia] had led the previous Viceroy, Lord Harding, to worry about the “risks involved in denuding India of troops.”[80] Revolutionary violence had already been a concern in British India, and outlines of collaboration with Germany were being identified by British intelligence. Consequently in 1915, the Government of India passed the Defence of India Act to strengthen its powers during what it saw was a time of increased vulnerability. This act allowed it to intern politically dangerous dissidents without due process and added to the power it already had – under the 1910 Press Act – to imprison journalists without trial and to censor the press.[83] Now, as constitutional reform began to be discussed in earnest, the British began to consider how new moderate Indians could be brought into the fold of constitutional politics and simultaneously, how the hand of established constitutionalists could be strengthened.[83] However, since the Government of India wanted to check the revolutionary problem, and since its reform plan was devised during a time when extremist violence had ebbed as a result of increased governmental control, it also began to consider how some of its war-time powers could be extended into peace time.[83]

Consequently in 1917, even as Edwin Montagu announced the new constitutional reforms, a sedition committee chaired by a British judge, Mr. S. A. T. Rowlatt, was tasked with investigating revolutionary conspiracies and the German and Bolshevik links to the violence in India,[84][85][86] with the unstated goal of extending the government's war-time powers.[82] The Rowlatt committee presented its report in July 1918 and identified three regions of conspiratorial insurgency: Bengal, the Bombay presidency, and the Punjab.[82] To combat subversive acts in these regions, the committee recommended that the government use emergency powers akin to its war-time authority. These powers included the ability to try cases of sedition by a panel of three judges and without juries, exaction of securities from suspects, governmental overseeing of residences of suspects,[82] and the power for provincial governments to arrest and detain suspects in short-term detention facilities and without trial.[87]

With the end of World War I, there was also a change in the economic climate. By year’s end 1919, 1.5 million Indians had served in the armed services in either combatant or non-combatant roles, and India had provided £146 million in revenue for the war.[88] The increased taxes coupled with disruptions in both domestic and international trade had the effect of approximately doubling the index of overall prices in India between 1914 and 1920.[88] Returning war veterans, especially in the Punjab, created a growing unemployment crisis[89] and post-war inflation led to food riots in Bombay, Madras, and Bengal provinces.[89] This situation was made only worse by the failure of the 1918-19 monsoon and by profiteering and speculation.[88] The global influenza epidemic and the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 added to the general jitters; the former among the population already experiencing economic woes,[89] and the latter among government officials, fearing a similar revolution in India.[90]

To combat what it saw as a coming crisis, the government now drafted the Rowlatt committee's recommendations into two Rowlatt Bills.[87] Although the bills were authorised for legislative consideration by Edwin Montagu, they were done so unwillingly, with the accompanying declaration, “I loathe the suggestion at first sight of preserving the Defence of India Act in peace time to such an extent as Rowlatt and his friends think necessary.”[82] In the ensuing discussion and vote in the Imperial Legislative Council, all Indian members voiced opposition to the bills. The Government of India was nevertheless able to use of its "official majority" to ensure passage of the bills early in 1919.[82] However, what it passed, in deference to the Indian opposition, was a lesser version of the first bill, which now allowed extrajudicial powers, but for a period of exactly three years and for the prosecution solely of “anarchical and revolutionary movements”, dropping entirely the second bill involving modification of the Indian Penal Code.[82] Even so, when it was passed the new Rowlatt Act aroused widespread indignation throughout India, which culminated in the infamous Jallianwala Bagh massacre and brought Mohandas Gandhi to the forefront of the nationalist movement.[87][92]

Meanwhile, Montagu and Chelmsford themselves finally presented their report in July 1918 after a long fact-finding trip through India the previous winter.[93] After more discussion by the government and parliament in Britain, and another tour by the Franchise and Functions Committee for the purpose of identifying who among the Indian population could vote in future elections, the Government of India Act of 1919 was passed in December 1919.[93] The new Act (also known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms) enlarged both the provincial and Imperial legislative councils and repealed the Government of India’s recourse to the “official majority” in unfavorable votes.[93] Although departments like defence, foreign affairs, criminal law, communications and income tax were retained by the Viceroy and the central government in New Delhi, other departments like public health, education, land-revenue and local self-government were transferred to the provinces.[93] The provinces themselves were now to be administered under a new dyarchical system, whereby some areas like education, agriculture, infrastructure development, and local self-government became the preserve of Indian ministers and legislatures, and ultimately the Indian electorates, while others like irrigation, land-revenue, police, prisons, and control of media remained within the purview of the British governor and his executive council.[93] The new Act also made it easier for Indians to be admitted into the civil service and the army officer corps.

A greater number of Indians were now enfranchised, although, for voting at the national level, they constituted only 10% of the total adult male population, many of whom were still illiterate.[93] In the provincial legislatures, the British continued to exercise some control by setting aside seats for special interests they considered cooperative or useful. In particular, rural candidates, generally sympathetic to British rule and less confrontational, were assigned more seats than their urban counterparts.[93] Seats were also reserved for non-Brahmins, landowners, businessmen, and college graduates. The principal of “communal representation”, an integral part of the Minto-Morley reforms, and more recently of the Congress-Muslim League Lucknow Pact, was reaffirmed, with seats being reserved for Muslims, Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, and domiciled Europeans, in both provincial and Imperial legislative councils.[93] According to the census of 1931, the number of Europeans was 168,134.[94] The Montagu-Chelmsford reforms offered Indians the most significant opportunity yet for exercising legislative power, especially at the provincial level; however, that opportunity was also restricted by the still limited number of eligible voters, by the small budgets available to provincial legislatures, and by the presence of rural and special interest seats that were seen as instruments of British control.[93] Its scope was, however, unsatisfactory to the Indian political leadership, famously expressed by Annie Beasant as something "unworthy of England to offer and India to accept".[95]

In 1935, after the Round Table Conferences, the British Parliament approved the Government of India Act of 1935, which authorised the establishment of independent legislative assemblies in all provinces of British India, the creation of a central government incorporating both the British provinces and the princely states, and the protection of Muslim minorities.[67] At this time, it was also decided to separate Burma from British India in 1937, to form a separate crown colony. The future Constitution of independent India would owe a great deal to the text of this act.[96] The act also provided for a bicameral national parliament and an executive branch under the purview of the British government. Although the national federation was never realised, nationwide elections for provincial assemblies were held in 1937. Despite initial hesitation, the Indian National Congress took part in the elections and won victories in seven of the eleven provinces of British India,[97] and Congress governments, with wide powers, were formed in these provinces. In Britain, these victories were to later turn the tide for the idea of Indian independence.[97]

World War II

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, declared war on India’s behalf without consulting Indian leaders, leading the Congress provincial ministries to resign in protest. The Muslim League, in contrast, supported Britain in the war effort; however, it now took the view that Muslims would be unfairly treated in an independent India dominated by the Congress.

The British government—through its Cripps' mission—attempted to secure Indian nationalists' cooperation in the war effort in exchange for independence afterwards; however, the negotiations between them and the Congress broke down. Gandhi, subsequently, launched the “Quit India” movement in August 1942, demanding the immediate withdrawal of the British from India or face nationwide civil disobedience. Along with all other Congress leaders, Gandhi was immediately imprisoned, and the country erupted in violent demonstrations led by students and later by peasant political groups, especially in Eastern United Provinces, Bihar, and western Bengal. The large war-time British Army presence in India led to most of the movement being crushed in a little more than six weeks;[98] nonetheless, a portion of the movement formed for a time an underground provisional government on the border with Nepal.[98] In other parts of India, the movement was less spontaneous and the protest less intensive, however it lasted sporadically into the summer of 1943.[99]

With Congress leaders in jail, attention also turned to Subhas Bose, who had been ousted from the Congress in 1939 following differences with the more conservative high command;[100] Bose now turned to the Axis powers for help with liberating India by force.[101] With Japanese support, he organised the Indian National Army, composed largely of Indian soldiers of the British Indian army who had been captured at Singapore by the Japanese. From the onset of the war, the Japanese secret service had promoted unrest in South east Asia to destabilise the British war effort,[102] and came to support a number of puppet and provisional governments in the captured regions, including those in Burma, the Philippines and Vietnam, the Provisional Government of Azad Hind (Free India), presided by Bose.[103] Bose's effort, however, was short lived; after the reverses of 1944, the reinforced British Indian Army in 1945 first halted and then reversed the Japanese U Go offensive, beginning the successful part of the Burma Campaign. Bose's Indian National Army surrendered with the recapture of Singapore, and Bose died in a plane crash soon thereafter. The trials of the INA soldiers at Red Fort in late 1945 however caused widespread public unrest and nationalist violence in India.[104]

Independence and partition

In January 1946, a number of mutinies broke out in the armed services, starting with that of RAF servicemen frustrated with their slow repatriation to Britain.[105] The mutinies came to a head with mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy in Bombay in February 1946, followed by others in Calcutta, Madras, and Karachi. These mutinies found much public support in India then gripped by the Red Fort Trials, and had the effect of spurring the new Labour government in Britain to action, and leading to the Cabinet Mission to India led by the Secretary of State for India, Lord Pethick Lawrence, and including Sir Stafford Cripps, who had visited four years before.[105]

Also in early 1946, new elections were called in India in which the Congress won electoral victories in eight of the eleven provinces.[106] The negotiations between the Congress and the Muslim League, however, stumbled over the issue of the partition. Muhammad Ali Jinnah proclaimed 16 August 1946, Direct Action Day, with the stated goal of highlighting, peacefully, the demand for a Muslim homeland in British India. The following day Hindu-Muslim riots broke out in Calcutta and quickly spread throughout India. Although the Government of India and the Congress were both shaken by the course of events, in September a Congress-led interim government was installed, with Jawaharlal Nehru as united India’s prime minister.

Later that year, the Labour government in Britain, its exchequer exhausted by the recently concluded World War II, and conscious that it had neither the mandate at home, the international support, nor the reliability of native forces for continuing to control an increasingly restless India,[107][108] decided to end British rule of India, and in early 1947 Britain announced its intention of transferring power no later than June 1948.

As independence approached, the violence between Hindus and Muslims in the provinces of Punjab and Bengal continued unabated. With the British army unprepared for the potential for increased violence, the new viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, advanced the date for the transfer of power, allowing less than six months for a mutually agreed plan for independence. In June 1947, the nationalist leaders, including Nehru and Abul Kalam Azad on behalf of the Congress, Jinnah representing the Muslim League, B. R. Ambedkar representing the Untouchable community, and Master Tara Singh representing the Sikhs, agreed to a partition of the country along religious lines. The predominantly Hindu and Sikh areas were assigned to the new India and predominantly Muslim areas to the new nation of Pakistan; the plan included a partition of the Muslim-majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal.

Many millions of Muslim, Sikh, and Hindu refugees trekked across the newly drawn borders. In Punjab, where the new border lines divided the Sikh regions in half, massive bloodshed followed; in Bengal and Bihar, where Gandhi's presence assuaged communal tempers, the violence was more limited. In all, anywhere between 250,000 and 500,000 people on both sides of the new borders died in the violence.[109] On 14 August 1947, the new Dominion of Pakistan came into being, with Muhammad Ali Jinnah sworn in as its first Governor General in Karachi. The following day, 15 August 1947, India, now a smaller Union of India, became an independent country with official ceremonies taking place in New Delhi, and with Jawaharlal Nehru assuming the office of the prime minister, and the viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, staying on as its first Governor General.

See also

- Imperialism in Asia

- Colonialism

- British Empire

- British rule in India for other periods when parts of India were under British rule.

- India Office

- Colonial India

- Historiography of the British Empire

- Indian independence movement

- List of Indian Princely States

- List of Indian Federal Legislation

- Governor-General of India

- Commander-in-Chief of India

- British Indian Army

- Indian Civil Service

- Order of the Indian Empire

- Anglo-Indian

- Anglo-Burmese people

- Macaulayism

Notes

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1989: from Skr. rāj: to reign, rule; cognate with L. rēx, rēg-is, OIr. rī, rīg king (see RICH).

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1989. "b. spec. the British dominion or rule in the Indian sub-continent (before 1947). In full, British raj.

- ↑ *Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1989. Examples: 1955 Times 25 Aug. 9/7 It was effective against the British raj in India, and the conclusion drawn here is that the British knew that they were wrong. 1969 R. MILLAR Kut xv. 288 Sir Stanley Maude had taken command in Mesopotamia, displacing the raj of antique Indian Army commanders. 1975 H. R. ISAACS in H. M. Patel et al. Say not the Struggle Nought Availeth 251 The post-independence régime in all its incarnations since the passing of the British Raj. For the latter usage, see: Google Scholar references: ("British Raj" in the primary sense of "British India," i.e. "regions of India under British rule") 1. "The important case of Islamic economics was a consciously constructed effort arising directly out of the anti-colonial struggle in the British Raj" 2 "... time" (1882: v). In keeping with the purpose of the Gazetteer (and indeed all such Gazetteers published for provinces in the British Raj), Atkinson's treatment ..." 3. "... Robert D’Arblay Gybbon-Monypenny, who had been born in the British Raj and educated at Sandhurst, afterwards seeing active service in the First World War ..." 4. "... In contrast, during the independence struggle in the British raj, the emphasis had always been on nationalism..." ("British Raj" in the second sense of "British India," i.e. "the British in India") 5. "Koch and the Europeans were entertained at clubs in the British Raj from which native Indians (called "wogs" for "worthy oriental gentleman") were excluded. ..." 6. "... prejudice and vindictiveness towards one's own race and, especially, toward someone of a different race who, as a servant in the British Raj, occupies a ..."

- ↑ First the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland then, after 1927, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

- ↑ "Nepal." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008.

- ↑ "Bhutan." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008.

- ↑ "Sikkim." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 5 August 2007 <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-46212>.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, pp. 59-60

- ↑ 1. Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume IV, published under the authority of the Secretary of State for India-in-Council, 1909, Oxford University Press. page 5. Quote: "The history of British India falls, as observed by Sir C. P. Ilbert in his Government of India, into three periods. From the beginning of the seventeenth century to the middle of the eighteenth century the East India Company is a trading corporation, existing on the sufferance of the native powers and in rivalry with the merchant companies of Holland and France. During the next century the Company acquires and consolidates its dominion, shares its sovereignty in increasing proportions with the Crown, and gradually loses its mercantile privileges and functions. After the mutiny of 1857 the remaining powers of the Company are transferred to the Crown, and then follows an era of peace in which India awakens to new life and progress." 2. The Statutes: From the Twentieth Year of King Henry the Third to the ... by Robert Harry Drayton, Statutes of the Realm - Law - 1770 Page 211 (3) "Save as otherwise expressly provided in this Act, the law of British India and of the several parts thereof existing immediately before the appointed ..." 3. Edney, M.E. (1997) Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India, 1765-1843, University of Chicago Press. 480 pages. ISBN 9780226184883 4. Hawes, C.J. (1996) Poor Relations: The Making of a Eurasian Community in British India, 1773-1833. Routledge, 217 pages. ISBN 0700704256.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. II 1908, p. 463,470 Quote1: "Before passing on to the political history of British India, which properly begins with the Anglo-French Wars in the Carnatic, ... (p.463)" Quote2: "The political history of the British in India begins in the eighteenth century with the French Wars in the Carnatic. (p.471)"

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 60

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 46

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV 1907, p. 56

- ↑ Kashmir: The origins of the dispute, BBC News, 16 January 2002

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Moore 2001a, pp. 424-426

- ↑ Moore 2001a, p. 424

- ↑ Brown 1994, p. 96

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Moore 2001a, p. 426

- ↑ Moore 2001a, p. 426, Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 104

- ↑ Quoted in Moore 2001a, p. 426

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 76, Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 104, Spear 1990, p. 149

- ↑ Bayly 1990, p. 195

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 72, Bayly 1990, p. 72

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Spear 1990, p. 147

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Spear 1990, pp. 147-148

- ↑ European Madness and Gender in Nineteenth-century British India. Social History of Medicine 1996 9(3):357-382.

- ↑ Robinson, Ronald Edward, & John Gallagher. 1968. Africa and the Victorians: The Climax of Imperialism. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday [1]

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts. 1. Verso, 2000. ISBN 1859847390 pg 7

- ↑ Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom. ISBN 0385720270 ch 7

- ↑ Hall-Matthews 2008, p. 1

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 478

- ↑ Cholera- Biological Weapons

- ↑ The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State, By G. William Beardslee

- ↑ INFECTIOUS DISEASES: Plague Through History, sciencemag.org

- ↑ Malaria - Medical History of British India, National Library of Scotland

- ↑ "Biography of Ronald Ross". The Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1902/ross-bio.html. Retrieved 15 Jun. 2007.

- ↑ Leprosy - Medical History of British India, National Library of Scotland

- ↑ Smallpox History - Other histories of smallpox in South Asia

- ↑ Feature Story: Smallpox

- ↑ Smallpox and Vaccination in British India During the Last Seventy Years, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1945 January; 38(3): 135–140.

- ↑ Smallpox - some unknown heroes in smallpox eradication, Indian Journal of Medical Ethics

- ↑ Sir JJ Group of Hospitals

- ↑ Rajat Kanta Ray, "Indian Society and the Establishment of British Supremacy, 1765-1818," in The Oxford History of the British Empire: vol. 2, The Eighteenth Century" ed. by P. J. Marshall, (1998), pp 508-29

- ↑ Professor Ray agrees that the East India Company inherited an onerous taxation system that took one-third of the produce of Indian cultivators.

- ↑ P.J. Marshall, "The British in Asia: Trade to Dominion, 1700-1765," in The Oxford History of the British Empire: vol. 2, The Eighteenth Century" ed. by P. J. Marshall, (1998), pp 487-507

- ↑ The Regulating Act - 1773

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 Ludden 2002, p. 133

- ↑ Ludden 2002, p. 135

- ↑ Ludden 2002, p. 134

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Robb 2004, pp. 126-129

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Peers 2006, pp. 45-47

- ↑ Tomlinson 1993, p. 43

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 47, Brown 1994, p. 65

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Brown 1994, p. 67

- ↑ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 79

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay 2004, pp. 169-172 Bose & Jalal 2003, pp. 88-103 Quote: "The 1857 rebellion was by and large confined to northern Indian Gangetic Plain and central India.", Brown 1994, pp. 85-87, and Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 100-106

- ↑ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 101

- ↑ Brown 1994, p. 88

- ↑ Metcalf 1991, p. 48

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay 2004, p. 171, Bose & Jalal 2003, p. 90

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay 2004, p. 172, Bose & Jalal 2003, p. 91, Brown 1994, p. 92

- ↑ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 102

- ↑ Bose & Jalal 2003, p. 91, Metcalf 1991, Bandyopadhyay 2004, p. 173

- ↑ Brown 1994, p. 92

- ↑ (Stein 2001, p. 259), (Oldenburg 2007)

- ↑ (Oldenburg 2007), (Stein 2001, p. 258)

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 (Oldenburg 2007)

- ↑ (Stein 2001, p. 258)

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 (Stein 2001, p. 260)

- ↑ (Stein 2001, p. 260) Quote: "The British knew about Indian famines well before the East India Company assumed political responsibility for India. Peter Mundy, an early seventeenth-century Company agent, reported a devastating series of bad harvests and food shortages in Gujarat and elsewhere in western India, which drove cultivators and artisans to migrate, some making their way a thousand miles to the southern tip of India, where they continue to live. Mundy described the responses of the Mughal governor of the province, ..., he noted with appreciation the free food distributions ordered by Emperor Shah Jahan."

- ↑ Angus Maddison, The World Economy, pages 109-112, (2001)

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 R.R. Bhandari (2005). Indian Railways: Glorious 150 years. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 1–19. ISBN 81-230-1254-3.

- ↑ "First train ran between Roorkee and Piran Kaliyar". National News. The Hindu. 10 Aug. 2002. http://www.hinduonnet.com/2002/08/10/stories/2002081000040800.htm. Retrieved 5 Jan. 2009.

- ↑ Babu, T. Stanley (2004). "A shining testimony of progress". Indian Railway Board. p. 101.

- ↑ Thorner, Daniel (2005). "The pattern of railway development in India". In Kerr, Ian J.. Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 80–96. ISBN 0195672925.

- ↑ Hurd, John (2005). "Railways". In Kerr, Ian J.. Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 147–172–96. ISBN 0195672925.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 R.R. Bhandari (2005). Indian Railways: Glorious 150 years. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 44–52. ISBN 81-230-1254-3.

- ↑ Awasthi, Aruna (1994). History and development of railways in India. New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications. pp. 181–246.

- ↑ Wainwright, A. Marin (1994). Inheritance of Empire. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 48. ISBN 9780275947330. http://books.google.com/books?id=1wERzXx94c8C&pg=PA48.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 80.3 Brown 1994, pp. 197-198

- ↑ Olympic Games Antwerp 1920: Official Report, Nombre de bations representees, p. 168. Quote: "31 Nations avaient accepté l'invitation du Comité Olympique Belge: ... la Grèce - la Hollande Les Indes Anglaises - l'Italie - le Japon ..."

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 82.5 82.6 82.7 82.8 82.9 Brown 1994, pp. 203-204

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 Brown 1994, pp. 201-203

- ↑ Lovett 1920, p. 94, 187-191

- ↑ Sarkar 1921, p. 137

- ↑ Tinker 1968, p. 92

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 Spear 1990, p. 190

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 Brown 1994, pp. 195-196

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Stein 2001, p. 304

- ↑ Ludden 2002, p. 208

- ↑ Report of Commissioners, Vol I, New Delhi, p 105

- ↑ Patil, V.S.. Subhas Chandra Bose, his contribution to Indian nationalism. Sterling Publishers, 1988.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 93.3 93.4 93.5 93.6 93.7 93.8 Brown 1994, pp. 205-207

- ↑ "Public policy and economic development: essays in honour of Ian Little". Maurice FitzGerald Scott, Deepak Lal (1990). Oxford University Press. p.363. ISBN 0198285825

- ↑ Chhabra 2005, p. 2

- ↑ (Low 1993, pp. 40, 156)

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 (Low 1993, p. 154)

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 (Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 206-207)

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay 2004, pp. 418-420

- ↑ Nehru 1942, p. 424

- ↑ (Low 1993, pp. 31-31)

- ↑ Lebra 1977, p. 23

- ↑ Lebra 1977, p. 31, (Low 1993, pp. 31-31)

- ↑ Chaudhuri 1953, p. 349, Sarkar 1983, p. 411,Hyam 2007, p. 115

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 (Judd 2004, pp. 172-173)

- ↑ (Judd 2004, p. 172)